- Home

- Robin Herrera

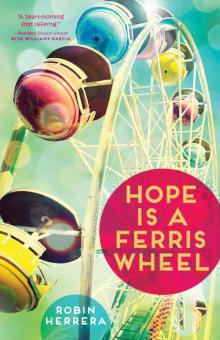

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel Read online

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Herrera, Robin.

Hope is a ferris wheel/Robin Herrera.

pages cm

Summary: After moving from Oregon to a trailer park in California, ten-year-old Star participates in a poetry club, where she learns some important lessons about herself and her own hopes and dreams for the future.

ISBN 978-1-4197-1039-1 (alk. paper)

[1. Trailer camps—Fiction.

2. Poetry—Fiction.

3. Clubs—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.H432136Ho 2014

[Fic]—dc23

2013026392

Text copyright © 2014 Robin Herrera Book design by Maria T. Middleton

“Dreams” from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright © 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to Random House LLC for permission.

Published in 2014 by Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Amulet Books and Amulet Paperbacks are registered trademarks of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Amulet Books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact [email protected] or the address below.

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

TO MY SISTER, JESSICA: OLDER, WISER, INFINITELY COOLER —R. H.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

CHAPTER 37

CHAPTER 38

CHAPTER 39

CHAPTER 40

CHAPTER 41

CHAPTER 42

CHAPTER 43

CHAPTER 44

CHAPTER 45

CHAPTER 46

CHAPTER 47

CHAPTER 48

CHAPTER 49

CHAPTER 50

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Everyone at Pepperwood Elementary knows that I live in Treasure Trailers, in the pink-tinted trailer with the flamingo hot-glued to the roof. The problem is, I only told four girls, the ones who were standing by me the first time we lined up for recess.

“Isn’t that next to the dump?” one of them asked.

“Well, there’s a fence,” I told them.

The third one behind me scowled and said, “My mom says only drug addicts live there.”

“There’re no drug addicts,” I said. “Well, maybe there’re drug addicts. I haven’t met everyone yet.”

“Hey,” said the girl in front of me. She must have overheard. “What’s the deal with your hair?”

“Oh, Gloria did it,” I said, holding out a strand so she could see the midnight blue streaks. “She went to beauty school. I use anti-frizz. I could get you some,” I offered. Gloria gets a good discount from Style Cuts, where she works, and she gets the expired stuff for free. We have tons of anti-frizz in the bathroom and practically every kind of conditioner.

“No thanks,” the girl said. “I don’t want a mullet.”

I heard three distinct giggles behind me. Those three girls were laughing at me. I couldn’t believe it.

But then I could, the next day, when everyone in class was asking me for anti-frizz. The thing was, they didn’t mean it. I mean, boys were asking me for it, and they couldn’t even get through the whole question without breaking into giggles. I had to go look up the word mullet when everyone started saying that, too.

“It’s not a mullet,” I told Winter, the day I found out what one was. “Mullets are flat and ugly.”

Winter sat me down at our built-in table and combed her fingers through my hair. My hair’s so thick, though, that I could hardly even feel it. “It’s because of all the different lengths,” Winter said. “It’s all short here and long here, so—”

“It’s a layered cut. That’s what Gloria called it. Why does everyone think it’s a mullet?”

Shrugging, Winter headed to the fridge. “I mean, it’s not like you told them you live in a trailer park,” she said, passing me a couple of oranges to peel.

“Of course I did.”

“Star!” Winter said as she slammed the fridge door shut. “You did not say that.”

“But—but—what about in Oregon?” I asked. “No one said I had a mullet there! And no one cared that I lived in a trailer park.”

“Yeah, because half the kids at school were from the trailer park! Haven’t you noticed anything different about California, Star?”

Yes, I had. There were no other kids at Treasure Trailers. There were a couple of babies and a million cats, but there was nobody even close to my age.

“You’re probably the only kid at school who lives in a trailer park,” Winter went on. “And everyone thinks trailer parks are full of gross people.”

I sighed, remembering what that girl’s mom had said. Was that what everyone thought? I started peeling the first orange. Winter peels them off in one long piece, but I haven’t been able to do that yet. I can only do it with mandarins. “So is that why they call me Star Trashy? Because we’re next to the dump?”

“It’s because we’re trailer trash, Star,” Winter said, taking the elastic out of her hair. “And Trashy kind of rhymes with Mackie.” She shook her head, and all her lovely black curls tumbled down past her shoulders.

It’s too bad my hair isn’t curly like hers—no one would think I had a mullet then. But I got Mom’s thick, straight hair that never needs volumizer. The only good thing about it is that it’s naturally black. Winter has to use dye.

“Do they call you Winter Trashy at Sarah Borne?”

“No. You know why? Because no one knows I live in a trailer park.” She plucked the orange out of my hand and had it peeled in ten seconds flat. “Anyway, even if they did, I doubt they’d make fun of me that much. There’re plenty of other delinquents to pick on. The pregnant girls get teased the most.”

“You’re not a delinquent,” I said.

“Yes, but I still go to delinquent school,” she said, and she started working on the second orange. I asked if they were going to let her take a creative writing class this semester, but she just scoffed, shaking her head. “They had to cancel the class. They were three students short of the minimum.”

That was too bad. I knew how much Winter wanted to take that class. It was the only thing she’d been looking forward to once Mom told her she couldn’t go back to public school yet. The worst thing was, they wouldn’t even let her start a new club, considering how the last one had turned out.

“Hey,” I said. “Maybe I could start a club.”

“Hey!” Winter repeated. “Just don’t do a writing club, or Mom will burst a blood vessel.”

“I won’t. I’ll think of something else.” I split the oranges into segments and divided them between us. They were a little old and a little dry, and Mom had accidentally picked up the seeded kind, so we had to spit our seeds out onto the table.

“I guess it’d be a good way to make friends,” Winter said. “I mean, I don’t talk to anyone from my old writing club anymore, but …” Frowning, she flicked an orange seed onto the linoleum. “I’m sure you won’t get yourself expelled.”

I told her I wouldn’t. “I have to think of something good, though. A club everyone will want to join. Then they’d have to be my friends, or I won’t let them in!” I pictured everyone’s faces and their clasped hands as they pleaded with me. As long as they were really sincere, I’d think about letting them join. “What do you think—” I started to ask Winter, but I was interrupted by the slam of a car door outside.

That was the end of our conversation. Winter raced to the top bunk with her backpack and kicked her combat boots off the side. A few seconds later Mom walked in, loaded down with groceries, followed by Gloria, still in her Style Cuts apron. “Heavenly Donuts!” Gloria yelled, loudly enough for the whole trailer park to hear. “I don’t remember it being this cold in Oregon!”

“Hey, Star, put these away, will you?” was the only thing Mom said to me before she noticed Winter. “I can see you sulking there, Winter,” she said, which I thought was pretty obvious—you can see every inch of the trailer from the front door, except for Mom’s room, which Winter wouldn’t be in anyway. “How was school today?”

And just like every day since the end of summer, Winter said nothing.

Mom straightened her glasses and said, “I just don’t get it,” before pulling a pizza out of the freezer. I got it, but I was busy putting the groceries away, and when I finally finished, Mom and Gloria were already talking about some woman who’d only tipped Gloria a dollar on a dye job. When I asked if that was bad, they both scoffed and threw their hands up in the air, so I decided to just stay quiet for the rest of the night.

I spend a lot of time at school staring at the back of Denny Libra’s head, wishing I had superpowers so my eyes could bore a hole right between his ears and see what Mr. Savage is writing on the whiteboard.

But it’s not like Denny doesn’t do the same thing to me when he turns around to pass papers back; he glares at my forehead like he’s trying to vaporize it. I’m sure he’d rather look at Delilah Manning, who sits behind me, but is it my fault that Mr. Savage made all the fifth-graders sit alphabetically?

Today was different, though. Staring into the void of Denny’s black hair, I finally came up with the perfect idea for a club. Mr. Savage was busy telling us about our vocabulary words, but I already knew what he wanted, so I turned my notebook to a fresh piece of paper and wrote, The Trailer Park Club.

It was absolutely perfect. I could teach our members about all the good things in trailer parks so that they’d stop thinking trailer parks were full of trash. (Although, with our flamingo-capped trailer being right next to the dump, sometimes trash just finds its way over the fence.) Maybe I could even figure out a way to talk about layered haircuts and how they are not mullets at all.

After school I asked Mr. Savage if I could hang a sign for my new club in the classroom. This was something I’d learned from Winter: if you’re asking for something, make sure you sound like you already have it.

Mr. Savage rubbed his beard for a few seconds and then asked, “You want to start a club? No one’s ever wanted to start a club.” Mr. Savage has only been a teacher for two years, but I couldn’t believe he’d never had anyone ask about clubs before. “You want to have it here?”

“At the school? Yes,” I said.

“In my classroom,” he said, now scratching his beard.

“Yeah.”

“You want me to supervise it?”

“I don’t need a supervisor,” I told him. “If you leave me the key, I’ll lock up when I’m done.” I used to do this for my third-grade teacher in Oregon so she could get to her second job on time. “I can leave the key in the drainpipe for you,” I added, pointing out the window.

“You know, I prefer to lock my own classroom.” The scratching increased, and behind my back, I crossed my fingers for luck. “I stay late on Wednesdays. Can you do Wednesdays?”

Wednesdays would be fine, but Winter says that you should always act like the first offer isn’t good enough, so I pretended to think about it, scratching my own chin and looking at the ceiling. After I counted to six in my head, I said, “I guess that’ll work.”

Mr. Savage went back to his computer, and I thought about asking if I could use it to make some posters. But Winter says you can’t ask for too much too soon, and she’s the club expert.

So I headed home. Maybe Winter had some of her old club flyers left, and maybe Mom would let me use the white-out she took from her last temp job so I could make some updates. Instead of THE CREATIVE WRITING CLUB, it’d say THE TRAILER PARK CLUB, maybe with a picture of a clean-looking trailer. And below that: NOW OPEN FOR MEMBERSHIP.

The pickup truck was in the driveway when I got to Treasure Trailers, which marked the first time in months that Winter had beaten me home. She was supposed to have lots of extra work to do after school, since she’d missed half her sophomore year in Oregon, but maybe she’d gotten it all done already. Maybe now that real school had started, she could be around more often.

I pulled open the doors and announced, “Hey, Winter! I started a Trailer Park Club!” But then my eyes adjusted to the darkness, and I saw that I was talking to an empty trailer. I checked the driveway again to make sure I hadn’t been seeing things, but, yup, the truck was still sitting there, empty cab and all. The trailer was truly empty, too—Winter wasn’t in the bathroom or in the closet or even in her bed. Slamming the screen door shut behind me, I climbed into Winter’s truck—she never locks the doors—and opened up the glove box.

It was stuffed with Winter’s stories, all folded into thick, tiny squares. A couple of them were typed, probably at the library or at school, but most she’d written in red pen. My favorite one wasn’t even in there—maybe her old principal still had it, if he hadn’t thrown it away or burned it or given it to the police.

Mom said I wasn’t allowed to read Winter’s stories anymore, since the characters in them have the misfortune of dying horrible deaths, like having all the blood explode out of their bodies. My favorite story was about Winter axing a bunch of zombies who were trying to eat her brain. She’d tried telling the principal that she was going to change the names later, since some of the zombies just happened to have the same names as some of her classmates, but I guess everyone had been freaking out, especially after they’d read Winter’s novella about the family of inbred mutant cannibals.

I don’t think Winter should have been expelled at all, especially over a story, but the school board didn’t agree. They wanted Winter to go to counseling, which we couldn’t pay for, so Mom decided we should just move instead and find a new school for Winter. We left as soon as Gloria got her beauty school diploma in June.

So all of Winter’s best stories were gone now, but she still had lots of others hidden away. I unfolded a good one called

“Hand It to You,” about this girl’s amputated hand trying to reattach itself to her arm every night. The ending always makes me laugh.

About three stories later, a knock on the driver’s-side window nearly made me scream. It was Winter, wearing her giant sunglasses and carrying a plastic dollar-store bag. “What’d you get?” I asked, when she opened the door and climbed in.

“Buncha candy,” she said, handing me a box of gummy bears. “Don’t let Mom see these.” And she stuffed her tiny story squares back into the glove box. “She’d probably make me do an extra semester at Sarah Borne if she found out. I’ve gotta get out of that place.” Her head sagged, and she held it in both hands as if, if she didn’t, it’d fall into her lap.

“You will,” I said, and as I reached out to put my hand on her shoulder, she started to cry. I couldn’t even remember the last time I’d seen Winter cry. She hadn’t shed a single tear when she got expelled, or even when Mom took away the card Dad had sent her for her thirteenth birthday. All the times I’d ever cried, Winter had held my hand or put her chin on my head and told me not to worry, that things would get better. So I did that—put my hand on Winter’s. “It’s okay,” I said.

But it wasn’t okay, and it didn’t help at all. Winter sat there sobbing, and I had nothing to say. I thought I could tell her about my club, but would that cheer her up, or would it make things even worse? Maybe it would remind Winter that she wasn’t allowed to form clubs anymore.

So I didn’t say anything, just kept my hand there, and eventually Winter’s huge shuddering breaths turned into soft sniffles. “It’s okay,” she said, even though I wasn’t the one crying. “I’m just … tired of being at that school. I’m tired of feeling like a loser.”

“You’re not a loser,” I told her. “You’re the coolest person I know!” She lifted her head the tiniest bit, so I fired off a couple more compliments. “You’re a really good writer, and your makeup’s always perfect, and … and …” I reached deep into my mind for something really, really good. “And Dad sent you a birthday card.”

She swiveled her head, and I saw my face reflected in her glasses. “Three years ago,” she said. “Geez, I almost forgot about that. Whatever—it wasn’t that big of a deal.”

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel