- Home

- Robin Herrera

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel Page 2

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel Read online

Page 2

“He never sent me a card,” I pointed out.

“Mom probably wouldn’t let him.” Shifting, Winter moved her hand so that it folded around mine. With her other hand, she took off her sunglasses and wiped away the stray tears on her cheeks, smudging her eyeliner. “She doesn’t even let him pay child support, which is just stupid.”

“I know,” I said. My hand felt warm and safe inside Winter’s. “But he did send you a card, even though he wasn’t supposed to. And he did give you the truck, when he could have just given it to Mom. Doesn’t that mean something?”

The cab was silent for several minutes. Mrs. O’Grady came out of her trailer with a sagging trash bag and jumped when she saw us just sitting there inside the truck. She crept back into her trailer, taking her bag with her.

“There was a note at the bottom of the card,” Winter said. “Right before he signed his name. He said, ‘Hope you and your sister are doing well.’ ” She squeezed my hand. “Do you think that means something?”

“He really said that?”

“Yup.”

“Really?”

“Yup.”

Heavenly Donuts! Mom was always saying Dad didn’t really care about us, that he was a nice man deep down but a very terrible father. That he would never be there for us when we really needed him, which was why it was better if he didn’t contact us at all.

But maybe that one little line proved that he cared, even if it was just the tiniest bit.

I wished I could hold that card in my hands to see the way he’d written it. Sloppily? Carefully? In slanting cursive that was hard to read?

If he’d gone through all that trouble to send Winter a card, it wasn’t so hard to believe he’d send me one someday. Maybe he was waiting until I turned thirteen, too. In that case, I’d only have to wait three more years.

Winter and I stayed in the cab even after it started to get dark. I didn’t get to work on my club flyers, but Winter helped me with all my vocabulary words, so I didn’t have to lug out the dictionary.

It was nice to know that the club was going so well. I mean, the hardest part was being allowed to start it, and that was already done. The flyers would be easy, and once everyone saw them, they’d join in a snip.

I just wished Winter’s problems would go away that easily, too.

Star Mackie

September 18

Week 1 Vocabulary Sentences

ABUNDANT. Like, lots of. Where I live, there are a lot of cats, like tumbleweeds in a desert, except here cats tumble around under your feet. Unlike tumbleweeds, cats make yowling sounds when you step on them. That is one of the many differences between cats and tumbleweeds.

ALTERNATIVE. This means a choice. Another choice. My sister goes to an alternative high school now, and it’s full of shoplifters and juvenile delinquents and pregnant girls. Alternative sounds like a choice, but it doesn’t seem like she had much of a choice to me. The juvies probably didn’t have a choice either.

CIRCUMSTANTIAL. Sometimes we watch Crime TV, and that is where I hear this word the most, and it’s always followed by “evidence.” I think it means that it makes someone look guilty but doesn’t actually prove anything, so it’s like how Mom and Gloria are always calling Dad a deadbeat jerk, but since I’ve never met him, I don’t know if that’s really true.

COVERT. Hidden, like a secret, or a spy. If I were a spy, I would want to be covert and not attract attention to myself, but I guess I’m not cut out to be a spy, because I already attracted attention to myself with my layered blue haircut. Most fifth-graders don’t have layered cuts or blue hair, but they are also not spies.

HYSTERICAL. This is my favorite. It means funny but also crazy. On the first day of school I heard some kids talking about Mrs. Feinstein, who’s this fourth-grade teacher (you probably know her, Mr. Savage) who worked in a canning factory in college, and one day—FWOOMP!—off went her pinkie, because it was too close to one of the cutters. Now she keeps it in a jar in her desk, everyone says, and sometimes she takes it out and waves it around at her students when they aren’t paying attention, and she says, “SEE WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU DON’T PAY ATTENTION?” Which is funny when you hear it from fourth-graders but probably not so funny when you’re sitting in the front row of Mrs. Feinstein’s class.

LANKY. I made a memory booster for this word. We had memory boosters at my old school, where you take each letter of the word and make it mean something different. So for LANKY it’s Long As Nine Knobby Yardsticks. I know the Knobby part doesn’t make sense, but I was thinking knobby like knees, because lanky people are usually skinny-legged, and their knees stick out, like Denny’s (you know him, Mr. Savage, because he sits right in front of me). Do you ever notice how far out of his desk his legs stick? I have noticed.

NEUTRAL. I asked my sister what this meant, and she said Switzerland, which makes no sense. Then she said it’s when you don’t pick a side, and sometimes that can be worse than picking the wrong side. Like in our home lately, there is my mom’s side and my sister’s side. I try to not be on any side, but secretly I’m always on my sister’s side. Things aren’t always her fault like Mom says.

POVERTY. I think people associate this with trailer parks, because they think, “Those people are too poor to afford a real house.” I guess that’s pretty much the meat of it, but I think there’s a difference between when my mom says why we live in a trailer park and when everyone else says why we live in a trailer park.

RELUCTANT. When you are reluctant, it means you don’t want to do something. I didn’t want to leave Oregon, especially because in California you have to pay sales tax on everything. You wouldn’t think eight percent is that big a deal, but it makes a pretty big difference when you buy something for $3.99, and you only have four dollars, and—surprise!—sales tax.

VEXATION. No one uses this word, ever, Mr. Savage. I know what it means, but I’m never going to use it, because it’s a pretty old word. I’m just telling you for your own good that no one ever says vexation unless they are about a hundred years old.

So, I did not turn in my vocabulary sentences. Everyone else did, but I didn’t, because I got the directions a hundred percent wrong.

We were supposed to use the word in a sentence. We were supposed to use the word in a sentence. Not a thousand sentences, the way I did. And most of my sentences didn’t even use the words!

I almost turned the homework in before I realized my mistake, but luckily Mr. Savage collected all the papers alphabetically (like our seating) and started with the fourth-graders before moving on to the fifth-graders. There are only eight fourth-graders, and they usually have different homework assignments, but we all have the same vocabulary words. I’ve never been in a class with two grades in it, but Pepperwood has a bunch of them.

Meg Anderson was first, so I had time to look over Denny’s shoulder to check out what he’d written, and I noticed that, first of all, he’d numbered all his sentences, and, second of all, each sentence was just that, one sentence, and third, the vocabulary words were underlined, and fourth, he had only used one sheet of paper instead of four.

I bet even the teachers at Sarah Borne wouldn’t have accepted my homework. They would have laughed and laughed and marked it with a big red check-minus. (Winter says the teachers can’t give out grades there.)

By the time Mr. Savage got to me, I had already crumpled up my four vocabulary pages and shoved them deep into my desk. I told him I’d left my paper at home, and he said, “Okay, just bring it next time, then.” After he walked away, a drop of sweat slithered its way down the back of my neck, and I was glad that at least some parts of my hair were long enough to hide it.

When recess started, I snuck over to the trash can by the door and threw my sentences away. Denny Libra glared at me the whole time and didn’t stop until I left the room.

I was so upset, I could only think of one word to describe how I felt.

Vexation.

On Thursday night Mom made macaroni

bake, the best thing she cooks. It’s macaroni and cheese, plus sliced-up hot dogs and bell peppers, with bread crumbs baked on top. We used the nice plates, and Gloria lit a candle and set it on the built-in table, and we all sat down to eat.

Winter shuffled the noodles around on her plate, not saying anything, as usual, until she uncovered a bit of hot dog. Then she pushed her plate away, folded her arms, and said, “I’m a vegetarian.”

Gloria dropped her fork. This was the first time Winter had spoken in front of Mom for nearly a month. Only Mom was unsurprised and kept eating like nothing weird was going on. All she said was, “Eat your food, Winter.”

Winter pushed her plate farther across the table, knocking over the saltshaker. “I don’t eat meat anymore. I find it vile.”

“Well, that would have been nice to know an hour ago, when I was cooking it,” Mom said. “And I don’t recall anyone putting in a request for fancy tofu dogs when we still had money on the food card.”

“I don’t eat meat,” Winter said again, and she crossed her arms.

Gloria grimaced, which she is very good at. Usually it’s funny to see a frown stretch across her face, but this time no one laughed. “Well, then,” she said to Mom, picking up her plate, “see you tomorrow, Carly.” And she left.

Once the door closed, Mom said to Winter, “Fine. But I’m not going to see good food wasted in this house.” She started picking out all the hot dog slices with her fingers and putting them on my plate, and even though I like hot dogs, my stomach cramped. I wondered why Winter hadn’t told me anything about being a vegetarian.

Once Mom was finished, Winter took a bite of the macaroni noodles, letting some of the cheese drip off first. “Ugh. I can still taste the meat.”

“Well, next time, Winter, I will know that I have to read your mind before I start dinner,” Mom said, her eyes narrowing and shrinking to the size of raisins. “Besides, hot dogs aren’t even real meat.”

I almost choked on the hot dog I had just swallowed.

“I’m gonna eat some cottage cheese,” Winter said, scooting past me. A few seconds later I heard her say, from the fridge, “Great. It’s expired.”

“It just expired yesterday,” Mom said. “And it’s not even really expired—that’s just a best-by date. You’ll be fine. I can’t count the number of times I’ve fed you girls ‘expired’ cheese.”

I almost choked on the macaroni I’d just swallowed.

Winter came back to the table juggling the tub of cottage cheese, a spoon, and a package of English muffins. I scooted over so she wouldn’t have to climb over me, but that meant Winter and Mom were now sitting right across from each other. Aside from the crinkling of plastic coming from Winter opening up the muffins, and the clatter of Mom’s fork against her plate, the trailer was silent.

“Um,” I said, wanting to change the subject, and Mom and Winter both looked at me. “What does Dad do?”

Mom’s eyes shrank even more. Talking about Dad is pretty much forbidden in the trailer. Or in front of Mom at all. Or even in front of Gloria, who will run and tell Mom instantly that her daughters are starting to get curious about their bloodline. “Don’t call him Dad. If you have to call him anything, call him your … your genetic donor.”

“What does our genetic donor do?” I asked, which made Winter snort.

Across the table, Mom’s shoulders hunched and she shrank into herself. The angrier she is, the smaller she gets. “He doesn’t do anything, Star. He isn’t fit to be a father.”

“I mean, what’s his job?” I asked as Mom shrank down still farther in her seat. I’d probably gone too far now, but I’d been wondering about Dad even more since Winter told me about the line on the birthday card. “Where does he work?”

Winter jumped right in. “What’s his favorite hobby? How much money does he make? How old is he?” We already knew the answer to the last one because Gloria let it slip once, but Mom had reached her shrinking limit. She grabbed all the food and plates from the table and threw them in the sink.

“Go to bed, both of you. If I hear one more word about that man, you’ll both be grounded. GO!”

Winter left, her combat boots stomping along the linoleum. I got our toothbrushes and changed into my pajamas, and the whole time Mom hunched over the sink, staring at the dishes full of food. I wanted to tell her I was sorry for bringing up Dad, but I didn’t want her getting any smaller than she already was.

Winter didn’t answer when I said good night, which made it hard to fall asleep, knowing she was mad, too.

After a while, I heard Mom’s footsteps creak across the trailer to her own bedroom. I stayed awake long after her light turned off, and long after her breathing slowed to a heavy wheeze. From the way Winter’s mattress shifted above me, I knew I wasn’t the only one awake.

Before the bell rang on Friday, Mr. Savage made an announcement to everyone. “Star is starting a club,” he said, holding his arm out to me. I stood up and waved a little bit. “It meets after school on Wednesdays, in this room,” he went on. “Star, why don’t you tell everyone about your club? What’s it called?”

I cleared my throat and said, “It’s called the Trailer Park Club.”

Someone coughed. It was one of the fourth-graders, I’m sure, because the eight of them sit in their own cluster by the door. I knew I should have run the name by Winter before announcing it.

Mr. Savage had his eyebrows halfway up his forehead. “The Trailer Park Club?” he asked, and I could tell that he was embarrassed just to say it.

“Yes,” I said, “but even if you don’t live in a trailer park, you can still come.”

Behind me, someone snorted. Well, maybe I wouldn’t let them join at all. I sat back down and heard people whispering all around. Pretending not to notice, I pulled out a piece of paper and started working on a flyer, with 3-D block letters that Winter had taught me how to make. I only got to TRA before the bell rang, since block letters are sort of time-consuming.

“Star,” Mr. Savage said as everyone left the room, “may I speak with you for a second?”

On the fourth-grade end of the room, Jenny Withagee lingered, stuffing papers into her purple backpack and glancing at me every other second. I skip-walked over to Mr. Savage’s desk, where he stood, his hands palms-down on his desk calendar.

“I think your club name may be a little off-putting,” he told me. “Maybe if you changed it to something else …”

I didn’t want to change the name. And I wished Mr. Savage would stop scratching his beard, which he was doing now; it made my face itch. I said nothing—another Winter tactic. She said it put the other person on the defensive, making them scramble for stuff to say, and then they looked so stupid that they just gave up.

“I just don’t know if anyone’s going to want to join,” Mr. Savage said, and he didn’t look stupid at all. He looked kind of sad … or like he was sad for me, which was even worse. I was about to abandon the whole silence plan and start pleading, when an airy voice called out, “I’ll be there!”

Jenny appeared next to me, grinning so hard her eyes almost disappeared. I was on the verge of saying, “Fifth-graders only.” Not because Jenny wears skirts to her ankles and has rub-on tattoos up and down her arms, which I don’t even care about, but because I don’t really know who she is, and I had this feeling that she wanted me to be happy that she’d just saved me from having my club taken away, even though she hadn’t.

Then I saw Mr. Savage’s face. I had no idea his eyebrows could go that high, but I was more angry at him for being so surprised than I was at Jenny for trying to be all heroic.

“See?” I told Mr. Savage. “One member already.”

He apologized and said that of course I didn’t have to change the name, and of course the Trailer Park Club was an excellent name. I smiled and walked out the door, glad that my club was saved but unglad that Jenny’s footsteps were following mine.

“So,” she said, once we were outside in the outdoor hallwa

y, dodging the few other kids who’d gotten out a bit late, “it’s on Wednesday? Should I bring anything?” Which bothered me, because I hadn’t even thought about bringing stuff myself. But I was saved from answering by, of all people, Denny Libra, who came out from behind one of the cement pillars holding up the hallway roof and curled his fingers around Jenny’s tattooed arm.

“Let’s go,” he said, and he started pulling her away, toward the playground. It was pretty obvious from the glare he was shooting me that he didn’t want her talking to me, which I thought was kind of creepy. I grabbed Jenny’s other arm and pulled her back, saying, “We’re talking about club stuff, donut-brain.”

“She’s not joining your club!” Denny shouted, so loudly that I had to let go. “You’re not joining her club,” Denny said to her, and he dragged her away, and she didn’t say anything, not one thing; she just followed him onto the blacktop.

I glanced back into the classroom to make sure Mr. Savage hadn’t seen, because I wasn’t sure he’d let me have my club if he knew the only member had just been yanked right out of it.

The first chance I got to talk to Winter alone since the world’s worst vocabulary sentences was on Saturday. Mom said she had a score to settle with the Food Bank, which meant she’d lost her card again and would have to argue a bag of food out of them. Gloria had a bunch of appointments booked, but she’d stopped by that morning to heat up a donut sandwich in our microwave. (Her microwave is haunted.)

When they were both gone, Winter told me she was going to the library.

“Can I go?” I asked.

She was still getting her coat and brushing on eye shadow, so she didn’t answer. Not until she put on her giant sunglasses. Then she said, “Are you coming or not?” And luckily I was already dressed.

In the truck, Winter tried to find a decent radio station, but she gave up when she almost hit Mrs. O’Grady’s trash cans. Besides, ever since the antenna fell off, the truck’s reception isn’t great.

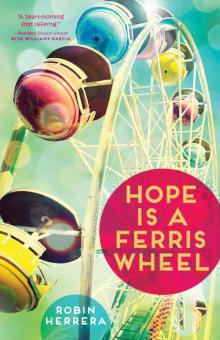

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel

Hope Is a Ferris Wheel